Episode Summary

After decades of neglect, there is finally a large and growing body of scholarship and journalism about the Religious Right, the powerful Christian Nationalist movement that rules the Republican Party from the heights of the Supreme Court bench down to the municipal voting precinct.

While there is a great deal of excellent research and reporting on the movement, it overwhelmingly tends to focus on the Christian Right as a political phenomenon and not as much as a religious one. As a result, we know a great deal about what the Christian Right does, but not why it does so.

Fortunately, David Hollinger, our guest in this episode is up to the task. He’s an emeritus professor at the University of California-Berkeley and the author of Christianity’s American Fate: How Religion Became More Conservative And Society More Secular, which demonstrates that the Christian Right was first a theological reaction against a progressive tradition of Christianity that began emerging in the middle of the 20th century.

Video

Transcript

MATTHEW SHEFFIELD: David, tell us, first of all, in the introduction, you make a remark that I think is very important and that is that a lot of people who are not religious tend to have no interest in hearing about religious doctrine and think it is of no consequence to them. You disagree with that in your introduction. Tell us why.

DAVID HOLLINGER: I think that because of the large role Christianity has played in the United States and continues to play, even though we're experiencing fairly rapid secularization right now. The ideas that are put forth in the name of Christianity and the people that fly the Christian flag have a lot of influence in the society.

So that's why everybody has a stake in who controls Christianity in the United States. And it has seemed to me, Matthew, that the literature that we have doesn't focus enough on this matter of what Christianity is and has been and where it's going. So you might say that we've got a lot of books, and many of them are very good, on Christian nationalism as such, and what its threats are to democracy, and we've got quite a few books closely allied on why did evangelicals flock to Trump.

Well, those are good literatures, but almost never do those books, and articles, and op-ed columns ask the question that I designed my book to answer. And that is how is it that Christianity, a massive and multifaceted aspect of American life since the founding of the country-- how did Christianity end up taking the form that it has now, the shape that it has now, and performing the role that it was now.

So I wanted to do a longer-term historical understanding of this and try to explain how we got there. And also to underscore the importance of religion in this.

So your opening point is very important to me and gets at something that's very basic to this book. I think that if there is any one takeaway that I would like people to have from this book regarding that question, the question of how Christianity takes this form, we need to remember that the evangelical Protestantism of our time, including its very strong Christian nationalist manifestation, we need to understand that all of this develops, not in a vacuum, but it develops as a process by which the people that we have come to call evangelicals, and call themselves that, have rejected an alternate version of Protestantism that was readily available to them.

Another version of Protestantism that took a much more capacious view of what Christianity is, that was much more responsive to a pluralistic society. And I'm talking of course about what we sometimes call the mainline, the old-fashioned Protestant establishment. All those Presbyterians and Episcopalians and Methodists and Lutherans that were very prominent in American life right down through the 1960s.

Now, this is a group that pretty much controlled what Protestantism was until relatively recently. Now, these people, these liberal Protestants, these ecumenical Protestants, these mainline Protestants, during the 1940s develop a very ambitious program for trying to respond to changes in modern life.

And they take a strong stand against Jim Crow and racism throughout the United States, and they take a strong stand against colonialism and imperialism abroad. They develop in the 1940s a program to develop a more cosmopolitan Protestantism. Now as they do this a lot of rank-and-file Protestants, especially those coming out of the fundamentalist tradition are uncomfortable with this.

So evangelicalism develops as a response to the liberal Protestants, the ecumenical Protestants campaign for a more cosmopolitan Protestantism.

Basically the evangelical formation as we have it today, this whole tradition leading to Christian nationalism, this develops as a safe harbor for White people who want to be counted as Christians without facing two challenges that the leadership of the mainline Protestants say you really have to face. 'You've got to face these challenges if you're going to be a Christian in the United States of the 1940s, fifties, sixties, and seventies.'

Two challenges, first challenge, all these liberal Episcopalians and so forth are say, first challenge is we live in an increasingly diverse society, an ethno-racially diverse society. We have to have a response to this somehow. We have to deal with it. We have to confront its injustices and do something about it.

Second challenge: We live in an increasingly science informed culture. So learning, education, science, very important to understand. And we have to have a religion, we have to have a version of Protestantism, a version of Christianity that takes this into account and responds to it.

So the old literal reading of the Bible, the sort of stuff that the fundamentalist used to do, that's just not viable anymore. So these are two challenges that the liberals are saying during the forties, fifties, and sixties got to do something about.

Now, many White people were uncomfortable with this. They are uncomfortable with having to face those challenges. Evangelicalism flourishes as a safe harbor for White Americans who do not want to face those challenges but are determined to be counted as Christians.

SHEFFIELD: So in terms of the history, the challenges, they're trying to reformat Christianity in America, but they're doing it in response in large measure to their contact with other traditions of religion, both Christian and non-Christian, which they encountered themselves through missionizing, through greater contact with Europeans.

And Christianity in Europe changed quite a bit before that. There's a saying that God died on the first day of the battle of the Somme in World War I. So Europe was going through a tremendous amount of religious change internally.

And you had the advent, especially in Germany, of scholarship that began to question the text of the Bible itself and the emergence of the documentary hypothesis such that, that it was evident, it became evident that the Bible especially the first several books of it were not the product of one person. In fact they were the product of many people. And it was a hodgepodge of traditions that were shoved together and--

HOLLINGER: Absolutely.

SHEFFIELD: And you do talk about also that when they were performing missionary work in other countries that were non-Christian, that that changed things for them as well. Can you talk about both of these two developments?

HOLLINGER: Yeah. If we were to, if we were to ask the question, why is it that these liberal Protestants became so determined in the 1940s to launch this campaign for a more causal Protestantism? There are several things in the background there. And one is the larger development of thought in Europe of the analysis of the Bible, the historicization of the Bible, the development of a liberal approach to Christianity, that's certainly going on.

And the leaders of these denominations are educated in seminaries during the 1920s and thirties where they learned all that stuff from the Germans. They really do learn that. But there are two more immediate things that really push these folks in the forties, and one of them is the foreign missionary project.

So beginning in the 1890s, especially when a lot of missionaries go abroad, the American missionary project goes back earlier to the 19th century, but from about 1890 to 1940 thousands of these American Protestants go to China, India, the Middle East, Japan. And the thing about them is that they come back, I mean, they went off, they went abroad to make the rest of the world more like American Protestants.

But while they're abroad, they tune in to a lot of different things and they become more respectful of diversity. They become more respectful of non-Christian religions. And so they, and especially their children, come back to the United States, come back to their churches, come back to their denominational assemblies, come back to their schools and colleges, and they criticize the provinciality of American life generally and of American Protestantism in particular.

So one thing that drives them is that they are determined to create a Protestantism that is more responsive to the diversity of the world. They discover through the missionary project that the expanse of humanity is much broader than just a lot of sort of vacant beings who are there just waiting for the benevolence and the instruction of American Protestants. Rather, these people have cultures and societies that are substantial and that we need to take account of, and from which we might even learn something from.

So that's one thing. Second thing that's more immediate, that's happening at the same time is Jewish immigration. So you have a small number of Jews in the United States, about 4 percent of the population in 1920, that continues down through the World War II era. But the thing about the Jewish migration is that it's culturally prominent Jews, unlike the Catholics, and there are many more Catholic immigrants than there are Jewish immigrants. The Jewish immigrants achieve rapid upward social mobility. And they also have a much higher level of literacy, much higher education than the Catholic immigrants do.

And many of them bring from the old-world artisanal skills and commercial experience. So as a result, you have a population of non-Christians who achieve rapid social mobility. And by 1920, between a fifth and a quarter of the population of New York is Jewish. Now this then continues down through the twenties and thirties, and then in the thirties when you get all of these intellectuals, all these people like Einstein and so forth coming in from Europe, that adds another dimension to this.

Now the point about these Jews is not so much that they're Jewish or even Judaic, and many of them are not Judaic actually, they're often very secular. The thing about them is, they're non-Christian. So for the first time in American history, you have a conspicuously present, a very prominent cultural presence in the United States that doesn't even share a Christian background.

Now, the Catholics, they're at least Christians, okay? So the notion of America as a Christian civilization, you can somehow accommodate that, even amid the rampant anti-Catholicism. That's very common among Anglo Protestants. But the thing about these Jews is that they, they're not even part of a Christian background.

So as a result, they constitute a challenge to Anglo-Protestant cultural hegemony in the United States. This is especially seen in the university. Jews are subject to a lot of discrimination before the 1950s and American universities to be sure, but they're prominent enough. So the most educated of these Protestants, the people that are running the Methodist Church, the people that are running the Episcopal church, the ones that are sensitive to what's going on in the missionary project, they are also sensitive to the diversification of American life.

Now at the same time, of course, they're aware of Jim Crow and the evils of discrimination against Black people. But what really hits these people afresh is the Jewish migration. So the Jewish migration and the missionary experience abroad are sort of twin influences to move these people in a more cosmopolitan direction.

And the way the Black population then comes in is that they realize that one of the first things they have to do is to address racial injustice in the United States. So they begin bringing in Black leaders. So people like Howard Thurman, Channing Tobias, Benjamin Mays. By the early 1940s, these really prominent Black intellectuals and Black preachers are brought into the leadership of the Federal Council of Churches.

Now, this whole project is pretty much a top-down operation in other words. So if you go into the average Methodist or Presbyterian church in Kentucky or Missouri, or even Pennsylvania or California, you're not going to find a really strong emphasis on doing away with Jim Crow.

You find some of that, but this is a top-down operation where, you might say, the ecumenical intelligentsia, educated biblical scholarship-- really struck with the significance of the missionary experience abroad and surrounded by all of these smart, well-educated, articulate Jews from the migration from Europe-- they're affected by all of this, and they want to do something about it. Because they think that the kind of Protestantism coming out of the fundamentalist tradition and being enunciated by some of the evangelicals of the forties just doesn't get it.

And it's indeed in response to this, in response to this campaign for a more cosmopolitan Protestantism developed in the wake of these conditions that I've described, that evangelicalism, as we know it comes into being as a point-by-point refutation and opposition to the ecumenical mainline liberal Protestants.

I'll give you some institutional examples. In 1942, we have founded the National Association of Evangelicals, which is designed as a lobby group to contest the influence of the liberal Protestants to the Federal Council of Churches. We have then in 1947, Fuller Theological Seminary established in California to counteract the Union Theological Seminary, Pacific School of Religion, Harvard Div school, all these liberal seminaries.

In 1956, you have the founding of Christianity Today founded to go against the Christian Century, the liberal Protestant house organ. So it's institutionally, and it's connected also with right wing political money.

It's interesting that Christianity Today gets its start when one of the big oil magnates, Howard Pew, gets fed up with the liberal Protestants because he doesn't think that they're fighting against the tradition of the New Deal.

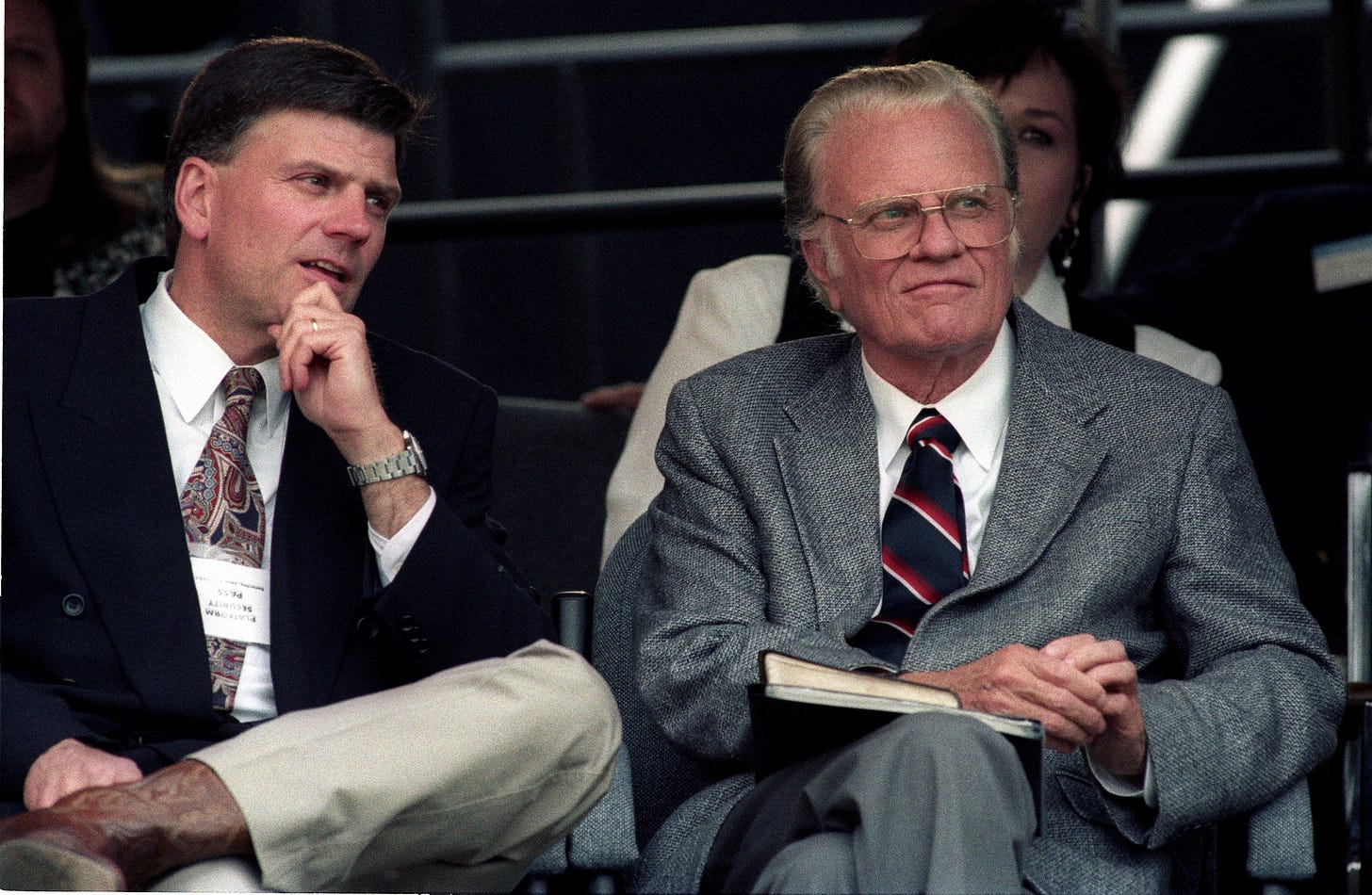

So Howard Pew takes all of his millions and millions of dollars, which he's been supporting the liberal Protestants and gives all this money over to Billy Graham. And Billy Graham's dad, and they found Christianity Today and they support a lot of these evangelical operations. So evangelicalism comes out of a religious conflict, no question about it, but it's also supported by right wing political money that understand very early on that this is a constituency that they can use.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah, exactly. And just give a little background on Howard Pew a little bit and who he was. And Howard, he was the only person involved in this, is it?

HOLLINGER: No, he wasn't, but he was the richest. And so, and he was also the most explicit.

So the National Council of Churches, which is a pretty strong operation in the 1950s with many denominations affiliated with it, they are taking a pretty strong egalitarian line and they support the traditions of the New Deal, and they think there's too much economic inequality in the United States.

And they like to quote the Sermon on the Mount so Jesus of Nazarus seems to think that everybody ought to be treated equally.

And Howard Pew, he thinks this is a mistake and so he organizes a lot of Presbyterian and Episcopalian businessmen and they constitute a committee, which he calls the National Lay Committee to influence the National Council of Churches to get them to adopt laissez-faire principles, we should not have government regulation of the economy at all.

So he presses this, and the leaders of the National Council of Churches won't have anything to do with this. So there, there's a fight on political grounds, and it's at this point that Pew moves his millions over to the other side.

Now, there are other people that are involved in this. There's actually a couple of very good books on that. I mean, Kevin Kruse has a very good book on the economic conservatives and the growth of the religious right. Darren Dochuk also has an excellent book on this. So that particular episode is quite out there and well discussed in the literature.

What I think is not understood as widely is that the religious motivations that a lot of the evangelical Protestants have at this time. Religiously, they're attacking an alternate religion, an alternate Protestantism. They're attacking a Protestantism that is friendly to the New Deal, that is friendly to African-Americans, that is critical of American foreign policy in the world.

In 1958, the National Council of Churches is by far the largest American organization to come out in favor of the diplomatic recognition of the People's Republic of China. Now, Howard Pew has a conniption.

I mean, at this point, a lot of the right-wing people, including Christianity Today, they're outraged Billy Graham's dad tries to get the Congress to investigate the leading Presbyterians that are in favor of the recognition of the diplomatic recognition of red China.

So there's a quarrel going on which involves a lot of these rich people, but it also fundamentally involves a different understanding of what Christianity should be. So Billy Graham comes along. He's very important all the way through the fifties and sixties, prominent even in the late forties.

But he's crucial to understanding this because Billy Graham says, you got to accept Christ, and people go to his altar to accept Christ. Well, what does that mean? Well above all, it means that you can accept Christ without worrying about Jim Crow. You can accept Christ without worrying about imperialism.

You can accept Christ without worrying about economic inequality. You can accept Christ without worrying about science. You can accept Christ without worrying about how the different books of the Bible were written. You can accept Christ if you're loyal to your spouse. You help your neighbors when they need it. You follow the Golden Rule. You avoid same sex relationships. You avoid pornography.

SHEFFIELD: And you say that you accept Jesus into your heart.

HOLLINGER: That's true. Yeah. So what I'm getting at is that there are a series of things that you can do that are actually not so demanding.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah.

HOLLINGER: Now, that brings up a important argument among scholars about the history of Protestantism during that period. I don’t think a lot of people who haven’t. Read about that history, even know about this controversy. But I’ll tell you that in 1972 there’s a book published on why evangelical churches are flourishing. This guy’s argument is that evangelicalism is flourishing because it makes demands. Ecumenical Protestantism is declining as it was by 1972, ecumenical Protestantism is declining because it doesn’t really make demands on people.

Now I’m arguing in my book that this is entirely wrong. So I reverse that, and I say ecumenical Protestantism meets these challenges and is more demanding and a lot of people would migrate over to the evangelical churches because the evangelical churches are not demanding that.

So the thesis I think should be that evangelical Protestantism is less demanding than ecumenical Protestantism. Evangelical Protestantism provides a safe harbor for people that want to avoid the stricter demands of that time.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. I’m glad you mentioned that. It’s the idea that the doctrines of Christ in terms of, paying attention to “the least of these thy brethren,” or ” doing unto others as you would have them do unto you,” that you have to consider that all the time in your actions and also in terms of who you support politically.

And that was not something that this emerging, what later became, overtly right wing, politicized religion, they didn’t want to accept that. And there’s a kind of a parallel when you look at they kind of say similar things to celebrities. They tell celebrities, shut up and sing. Don’t tell us about morality. Don’t tell us about– of course there’s a much greater irony in the fact that they’re telling pastors not to tell them about morality.

HOLLINGER: Well, and you have to remember that the evangelical line on these things is that all that’s politics, that’s not religion. So worrying about Jim Crow, that’s politics. And we shouldn’t get involved in that.

Whereas the ecumenicals are coming along and saying religion has been always embedded in politics. We can’t avoid a political challenge if we want to be true to our faith. So again and again, you would find evangelical preachers calling out the liberals for substituting politics for religion.

This is a constant theme that you hear all the way through. I think a very striking and emblematic episode for this is in 1963 after Martin Luther King Jr. gives his famous speech, that “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington after the big march on Washington. Billy Graham is asked what he thinks about this, and Graham says that the little white children and the little black children of Alabama will walk hand in hand only when Christ comes again.

So that’s making a religious obligation, but it’s so distant. So people don’t have to do anything as Christians now, because we don’t want to get religion involved in politics. But in the long run we know that racism is bad, but we also know that we’re not going to do anything to change it.

If we do anything, it’s going to be piecemeal, doesn’t amount to much. So yes, there’s a huge divide between ecumenicals and evangelicals having to do with a lot of these issues in the society. And the ecumenicals are saying, look, this is religious. It’s not something that’s apart from religion at all.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. And what’s kind of interesting, if we fast forward a little bit further, the Christian Right now kind of approaches things differently. In other words, they have taken that argument of, well, we need to apply our values in politics.

They now believe that currently.

HOLLINGER: Yeah.

SHEFFIELD: After actively disbelieving this doctrine–

HOLLINGER: That’s right.

SHEFFIELD: –earlier. And you can see it in the way that they’ve accepted the doctrine, but in an altered form.

HOLLINGER: That’s right.

SHEFFIELD: In regards to how they treat the subject of religious liberty and how they’ve redefined it. So can you talk about that a little bit, please?

HOLLINGER: Well, it’s certainly the case that when the Republican Party sees how valuable a constituency ecumenical Protestants can be, beginning with, really, in the Nixon period, especially Nixon and Reagan.

The Republican Party realizes that evangelical Protestants are a great resource for them. And as they continue to cultivate the evangelical Protestants, the evangelical Protestants realize that a way for them to influence the society more is to go along with the Republican Party. So this is something that grows all the way through the eighties, nineties, early 20th century, all the way down through the present.

And it’s facilitated by all this Republican power. Now the evangelicals in earlier times didn’t have that connection to political power, and it was easy for them to take the views that they did. Now they did try, it was interesting that in 1949 and again in 1954, evangelicals try to get God and Jesus written into the federal constitution of the United States.

So Christian nationalism has been around for a long time, and they did make this effort in that time, but they didn’t have anywhere near the clout that they’ve developed more recently. So now you have a Supreme Court and many people in the Congress that are quite happy with this expanded notion of religious liberty. And we see it in one of these court decisions after another.

SHEFFIELD: And it’s something now that they’ve continued. It is integral to how they do things. And what’s further fascinating about this acceptance, and revision, or reinterpretation of religious liberty and public morality is that the Christian right as a political force is overwhelmingly Protestant. But in terms of the intellectual operation and like the Supreme Court justices, the law professors, they tend to overwhelmingly be Catholic.

HOLLINGER: That’s right.

SHEFFIELD: And of the integralist persuasion. So can you talk a little bit about what is integralism, for those who don’t know what that is, and maybe talk about the history of right-wing Catholicism in this mix here?

HOLLINGER: Well, the Catholic tradition has always presented opportunities for Protestants to sort of expand on their notions of Natural Law, and their sense that society ought to be organized around these religious doctrines. Now, generally, Catholics have been content to attack the United States for this church-state separation. That’s a longstanding thing.

Catholics basically refused to accept church-state separation until the 1960s and 1970s. Then after that, thanks partly to Vatican II and the influence of the great Jesuit theologian John Murray, Catholics begin to be more active in American politics and to infuse indirectly, often Catholic doctrine.

The thing about these Supreme Court justices that we have now is not that they’re appointed as Catholics. It’s not that they arise formally as Catholics, but informally, they continue this old Catholic tradition of the priority of faith over what goes on in the world. So that’s something that has happened particularly the last few years, and it’s sort of ironic.

I mean, if you imagine, say at the time that Kennedy was running for president in 1960 as a Catholic candidate, now he of course renounced any connection between Catholicism and what he would do as president. If somebody would’ve said in 1960 that if we keep this up by the early 20th century, there’ll be six Catholics on the Supreme Court.

If you’d have said that in 1960, you’d have been blasted as a bigot. ‘What terrible prejudice!’ But it turns out that we now have six Catholics on the Supreme Court now, just how much their Catholicism influences– what they do is contested, I won’t quarrel about that. I just know that there’s a lot of literature which does attribute a lot of their views, a lot of the things that they do on the court to this, to this Catholic tradition.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. And there is kind of a somewhat of a Protestant analog, it’s very different in terms of what it says, but conceptually, as a Christian legal framework, you have a person who is very influential in the Protestant Christian Right, RJ Rushdoony.

So who was he? Because he also was very active and began his career in this moment.

HOLLINGER: Well, there’s a quite a few people that are pressing that Christians have an obligation to live out Christianity by taking over the world. Now, that’s a very different sense of what Christian obligation is from these liberals that I’ve been talking about, but there is this very strong sense of dominion. I mean that Christians are endowed with the authority by God to basically run the world so well —

SHEFFIELD: And that Jesus will not come back until they do.

HOLLINGER: That’s true. They do. So, so somebody like Josh Hawley, the Republican senator from Missouri, who got such notoriety for holding his fist up on January sixth. He argues straight out in his various lectures that Christ controls everything we have to bring all of the United States under the control of Christ. And this continues in a lot of other people in that tradition are arguing this as well.

And the basic text for that is Corinthians 10:5: “We shall take every thought captive and make it obedient to Christ.” And this comes up frequently under the guise of religious liberty. That it is religious liberty which gives us the right to control more and more of the country. So religious liberty as it expands gives people this chance to basically push other people around.

The other day there was a case, oh, this was actually, I guess last year, the new governor of Oklahoma made a public statement, basically giving Oklahoma to Christ. Now, this is a formal statement by an elected official. Now, this could happen in a place like Oklahoma because everybody is okay with it.

The understanding that Christian nationalism and American loyalty are all part of the same thing. Now, that’s wouldn’t happen in California or New York or Massachusetts or even Minnesota or Illinois, but there’s some parts of the country now where this kind of Christian Dominion has taken over and people do not have any qualms about saying it in public.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. And it’s tremendously ironic that when JFK was running for the first time, you had a lot of Republicans who were arguing for separation of church and state.

HOLLINGER: You did.

SHEFFIELD: And that this Catholic guy was perverting the American way by getting involved in that.

And, and now they’ve completely turned it on its end.

HOLLINGER: Right.

SHEFFIELD: And now believe the opposite of everything–

HOLLINGER: right.

SHEFFIELD: That they said formerly. Now to your point though on the religious liberty angle, you had talked about the increasing prominence of, of Jews in the mid 20th century, right?

There was a reason that so many German Jews who were trying to escape the Holocaust and French Jews, in particular those two countries, that they came to the United States over other countries. And that was because they saw the United States as uniquely safeguarding of religious freedom for Jews.

HOLLINGER: That’s right.

SHEFFIELD: And there’s some fascinating research that has been done looking in the journals of colonial American Jews, so immigrants to the United States from various countries who happen to be Jewish, and they’re writing back to their relatives in Europe.

And they’re saying: ‘This place is amazing. I cannot believe how great it is here. I can actually be Jewish and no one will discriminate me against me. I’m going to run for office and I don’t have to swear on the New Testament. I don’t have to say that I believe in Jesus. I don’t have to do any of those things. You guys should come here and check this out.’

HOLLINGER: Well, that’s a fascinating theme, and I recently read a book that illustrates that profoundly Roger Cohen, the great journalist, has a book called The Girl from Human Street, and it’s about his Jewish family originating originally from Lithuania. And they have a long diaspora in South Africa when they escape the pogroms of the 1890s. And different parts of this family end up in England, in Israel and South Africa in the United States. And Cohen narrates the various experiences and the book climaxes with his decision to leave England and come to the United States on very much the grounds that you’re talking about.

The United States, for all its easily enumerated prejudices and failures to achieve justice for a variety of peoples, nonetheless offers a more open environment, a more genuinely multicultural civic culture than you find in most other countries of the world.

So there is an impressive literature on that, and I think the Roger Cohen is as eloquent as any voice I’ve seen.

SHEFFIELD: We talked a little bit here in the discussion about race as a factor into this evolution. One of the things that is interesting in some of the contemporary research is that people– so the Public Religion Research Institute, PRRI recently did a survey about Christian nationalism, which had thousands of respondents.

One of the things that they found is that when you broke down the respondents by race and you measured their adherence to these ideas or sympathy to Christian nationalist ideas, the only racial group that was less prone to accepting them was Asian Americans, that Hispanic Americans, Black Americans, White Americans, they all had similar kind of percentages of people that had bought into these concepts.

And it’s making some people look at that. When you look at the election returns for 2020, Donald Trump actually decreased his vote share among White voters, and he increased it among Black and Hispanic voters. Do you see that Christian nationalism sort of penetrating back into Black and Hispanic communities as a way of sort of radicalizing them over to the right and as a method of protecting their religious opinions?

HOLLINGER: Well, I think that any constituency that strongly identifies as Christian, if you have people coming along and saying, ‘look, if you’re really Christian, you have to do things this way,’ that creates some tension. And particularly with the less educated of these people, there’s a strong appeal for that. So I can see that there might be some of these ethnic minority populations who would be subject to that.

But I looked at that report as well, a very interesting survey. I didn’t find the ethnic distinction so striking. I’m not sure that that is going to be such a big deal on this. But again, historians don’t like to predict the future, so I would be reluctant to hold forth too much on that.

I’m not sure that we should count out any ethnic group from the effort to get people to criticize Christian nationalism to see beyond it and to accept a democratic, inclusive, diverse society. I wouldn’t give up on any of them at this point. And I didn’t think that the survey data there was that scary.

So what’s scary is that so many the Republicans are devoted to Christian nationalism. And also a really striking thing about that survey, Matthew, is that the people that are most likely to be a Christian nationalist are those who go to church often, and there are a lot of people who identify as Christians but don’t go to church, and they tend to be less nationalists, less Christian nationalists.

That’s an interesting fact.

SHEFFIELD: Hmm. Yeah. Well, and a lot of these pastors have gotten radicalized, and there actually are operations designed solely to radicalize pastors by giving them free, amazing trips where they try to propagandize them. It’s really disturbing.

Alright, so we’ve talked about Protestants, we’ve talked about Catholics, we talked about Jews. One other group that did really play a large role in the creation of our contemporary Christian nationalism is Mormons.

So the Book of Mormon– and of course, as my listeners and viewers will know– I was born and raised as a fundamentalist Mormon. And in Mormonism, Christian nationalism is baked into Mormonism.

In the Book of Mormon, it is a literal doctrine that Christopher Columbus discovered America because Jesus helped him do it. And that this is a “choice land above all of other lands,” and that the only people who are allowed to live in the United States or this hemisphere, depending on who you ask, the only people that are allowed to live here by God must worship Jesus, must be Christian.

That’s in the Book of Mormon.

HOLLINGER: It’s a good reason for you to leave the Mormon church.

SHEFFIELD: But those doctrines were kind of abnormal for a while among most American Protestants. But during this period that we’re talking about here, the Early Cold War, those doctrines began to be extracted from Mormonism and injected into conventional evangelicalism through the work of the John Birch Society, through people like Ezra Taft Benson through people like Cleon Skousen, who is actually currently having a huge resurgence in popularity. So talk about the Mormonism aspect, please.

HOLLINGER: Well, I think that the Christian nationalism that we see among evangelicals today would be pretty strong even if there were no Mormonism. So I think that you’re correct, that that’s a tributary of it, the Mormon doctrines, when Mormons become respectable through Ezra Taft Benson, and people like that, that’s a tributary.

But many of the most prominent Mormons in political life have soft-pedaled that. [Mitt] Romney, for example, is not somebody who’s hardcore on that. So I would say that the Christian nationalism that you find within Mormonism is something that goes hot and cold, depending on the particular politician that’s pushing it.

And the state of Utah is quite distinctive. I mean, even Idaho doesn’t have as much of that ethno-religious homogeneity as Utah does. So I’m not sure that the Mormon phenomena is that large a factor in the whole picture. At least that would be a feeling that I would have about it.

SHEFFIELD: Okay. Yeah. Well, hey, that’s a fair point to make for sure. All right, so was there anything, another aspect of the book?

HOLLINGER: Yeah, there’s something I want to mention that I think this book of mine is a little different than a lot of the others on the shelf in that I do try to look upon American Christianity in a world historical frame.

Most of what is written about American Christianity is not only parochial, dealing just with the last 30, 40, 50 years, but also just dealing with the United States. Whereas if you understand Christianity as a world project that’s been going on for a couple thousand years and has many, many different varieties, we understand that its specific character always depends on who controls the local franchise, you might say.

And it amuses me and embarrasses me when you have people saying, well, Christian nationalism isn’t really Christian, and we know it’s not Christian, because that’s not consistent with what we read in the Bible. And then they’ll go back and they’ll read some stuff from the Book of James or from Matthew, from the Sermon on the Mount, and ‘this is Christianity.’

Okay, well, I’m sympathetic with those kinds of Christianity, but we need to remember that it’s not the Bible itself that’s driving that. It’s the cultural perspectives within which the Bible is interpreted. So people need to be reminded again and again, that among the most sophisticated students of biblical hermeneutics ever were the people that built the pro-slavery argument.

So if you want to see somebody who really knows their Bible and knows all the different languages in which it was written and read it very carefully. You can go to the pro-slavery argument. These people thought that the Bible justified slavery.

Now, we don’t believe that today, whether we’re secular or any kind of Christian believer, but the example is important for understanding, that we need to look at Christianity in the United States today in terms of who owns the franchise.

Now, the franchise in the middle decades of the 20th century, the franchise was held by these liberal ecumenical Protestants. The franchise has now largely gone over to the control of the evangelical Protestants, the white evangelical Protestants.

SHEFFIELD: Now you say, I’m sorry, you say franchise, what do you mean?

HOLLINGER: So the concept of franchise I’m using to remind us that what we count as Christianity is something that’s highly particular and is subject to the way it’s been articulated in Northwestern Europe, and especially then in the United States.

But that there are a whole variety of stuff. You look at the history of Christianity from the beginning, the Bible consists of 32,000 verses composed in many centuries apart by people that were in very different historical situations. So we need to get away from this idea that the Bible is somehow a bedrock and if only we could go back to that, then we would solve all these problems. ‘Get rid of Christian nationalism by going back to the Bible.’ Not true.

SHEFFIELD: Yeah. I agree with that. And the thing that I sometimes say to people who make similar remarks to me is that religions are like languages. They belong to the people who speak them.

HOLLINGER: Right.

SHEFFIELD: The people who are speaking the loudest their form of Christianity, well then, they are Christianity as far as anyone else knows.

HOLLINGER: That’s right.

SHEFFIELD: Okay. All right. Well, this has been a great conversation. We’ve been speaking with David Hollinger, he is the author of Christianity’s American Fate: How Religion Became More Conservative and Society Became More Secular. So I encourage everybody to check that out. Thanks for being here today, David.

HOLLINGER: Oh, well thanks very much. I’ve enjoyed it. I appreciate it, Matthew.

SHEFFIELD: All right, so that’s the program for today. I appreciate everybody who is a subscriber to Theory of Change and Flux. We really appreciate your help in getting these deep conversations about politics, religion, media, and technology, and getting them to a bigger audience as we’re expanding the show and to new platforms.

And of course, you can always manage your subscription on Patreon or on Substack, and I appreciate everybody who is doing that. You can always get more of this by going to flux.community as well, and I encourage you to do that.

Thanks very much. I’ll see you next time.

Share this post